Burial's Urban Darkness & Some Early Dubs

The impact of a single album over an entire style of music, and some early dubs

Prologue (a decidedly way too long one…)

Lately I’ve been taking a much needed break from all things Metal & Punk, which is what the majority of the articles I published through this newsletter is about. Don’t get me wrong though, there’s nothing I’ll ever like more than buzzsaw guitars, thundering bass, and frantic drums, but while I’ve indeed been into bands like Katharsis or Dawn for as long as I can remember on one side, I also reviewed records by artists coming from non-metal-adjacent backgrounds such as SPK, Herukrat and Tusen År Under Jord on the other. I’ve always been a huge fan of electronic music, most of which is often the complete opposite of the harder styles of rock music, and that led me to asking myself why that is many times, but I’ve only been able to gradually come up with a few educated guesses. The one I think makes the most sense is that my enjoyment of a specific style of music largely depends on the idea and the “intent” behind the music itself. Let me explain.

If you’re familiar with the works of bands such as, let’s say, Doom from the UK or Entombed from Sweden, you’ll notice how both Metal and Punk can get very dark and brooding if needed. That’s one of the reasons that got us the much-beloved and cartoonishly-exploited PMRC, the American association responsible for creating the logo that music stores throughout the United States would be forced to slap onto the CD cases of most of the albums coming out of the Metal, Punk and Hip-Hop underground between the mid-80s and the late 90s. Electronic music is no less, and that’s been proven countless times. Just take a look at the Japanese Noise scene, or even acts like Stalaggh. It hardly gets darker than hearing some poor schmuck scream their lungs out into a microphone.

All I really want to say is this: it doesn’t really matter whether you’re using guitars and drums instead of a synthesiser. There are other ways to communicate emotions through sound, especially if your goal is to make people uncomfortable. I mentioned Stalaggh in the previous paragraph: all their albums are made of is literally just people screaming their lungs into a microphone. That is it and that is enough for them to effectively communicate the idea and the intent behind their project. And here comes the main subject of this mess : Dubstep.

The sound of dark urban London

Ok, that probably didn’t come out sounding as good as I expected it to, did it? But bear with me. Even though most of us don’t remember it as such, Dubstep used to be synonymous with a pretty dark sound. As early dubstep aficionado Martin Clark, also known as Blackdown, described it on his blog as early as 2004 (!):

“if grime is the voice of angry urban London, dubstep is its primary echo, the sound of dread bass reflecting off decaying walls”

That’s a very apt description of what Dubstep originally sounded like. The genre started to gain some traction in the mid-2000s as a response to 90s UK Garage (or so I remember being told on music forums, I’m way too young to have any first-hand knowledge on the history of this kind of music) and I remember it instantly caught my attention the day I found out about it. There was something soothing in the half-time drum loops being played ad nauseam, in the endless array of synth sounds drenched in reverb and delay, in the Patois vocal samples. It all sounded so right, yet so… grim for some reason.

As a music genre, Dubstep managed to capture the sound of the tense, intense metropolis that it was born out of. The echoing sound of the rattling underground speeding through the concrete veins of the city, the nightly bus rides, and the less-than-ideal weather conditions that you’re forced to deal with most of the time.

In the following paragraphs we’ll be discussing an album that, over the course of a more than a decade, managed to become a defining influence on the genre. An album that has been able to show the world not just what Dubstep is, but what Dubstep can be.

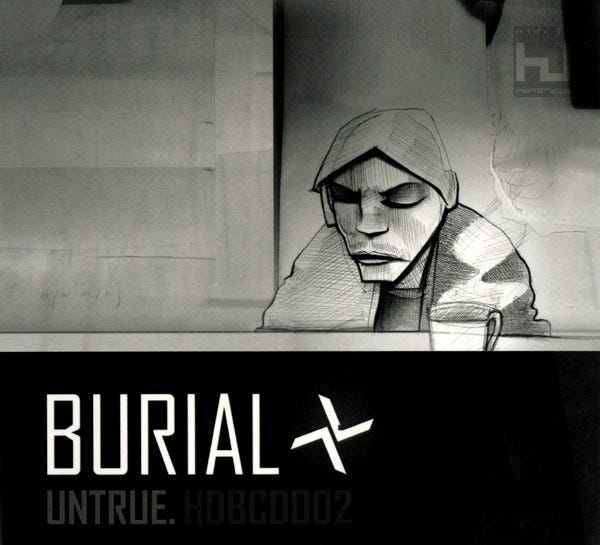

Burial - Untrue (Hyperdub, 2007)

Every genre of music is characterised by a selection of works that managed to have such a trailblazing impact on the genre, that they’ve gradually started to be deemed as “essential”. That’s the case of ‘Paranoid’ or ‘Sad Wings Of Destiny’ when it comes to 70s Metal, or ‘Enter the Wu-Tang’ and ‘All Eyez On Me’ when it comes to 90s Hip-Hop. When it comes to mid-2000s Dubstep, you may think of Skream’s self-titled debut album from 2006 or singles such as ‘Roll With The Punches’ by Peverelist or ‘Eyez’ by Mala as particularly influential, but in the vast majority of cases where you need to pinpoint a specific work and award him the title of genre-defining masterpiece of the Dubstep underground, everyone seems to always go back to one album in particular: Burial’s debut album ‘Untrue’, released in 2007 by Kode9’s UK-based independent powerhouse Hyperdub.

While it may be considered a standing stone of the Dubstep style, what Untrue really consists of is an amalgam of different sounds and style whose ultimate result is one of the most sonically diverse records to have ever been released in the scene to date. As shown by the extensive use of manipulated R&B and pop vocal samples, Burial doesn’t shy away from the Garage influences. Instead, he embraces them and implements the Garage sound into a sound that’s by and large a mishmash of samples from every medium you can possibly think of; songs, one-shot sound effects lifted off of old video games, old YouTube videos, you name it really. That’s very evident in tracks such as the album’s flagship song ‘Archangel’ and my personal favourite of the bunch titled ‘Near Dark’.

Along with this vast catalogue of sound sources, another thing that sets Untrue apart from most other Dubstep artists, both old and new, is his inherently ‘clunky’ and ‘un-tight’ sound. See, one thing you’ll notice once you try listening to Coki’s old white labels or the Loefah’s early works is that each and every single one of them sounds extremely clinical, especially if you pay attention to the rhythm section. If you’ve ever tried giving electronic music production a chance in your life, chances are you’ve heard of things such as drum machines and most importantly quantization, i.e. digital tools that essentially allow you to eliminate human imperfections in a drum pattern or a series of notes. Ok, now take all that and throw out the door because you won’t find that in this album. I really have no idea how Burial went about the production of Untrue, but you can very much tell each element in the drum section wasn’t altered or digitally messed with too much. Chances are he probably just dragged everything onto a sequencer and that was it.

Another thing that has to be noted about Burial’s sound on Untrue is that, while it has been long associated with Dubstep and often hailed as one of the genre’s finest productions to date, Burial is by no means a Dubstep artist - or at least he is not just that. The same guy who wrote Untrue in two weeks is also responsible for more upbeat and even breakbeat-oriented tracks such as ‘Stolen Dog’ from the Street Halo EP and ‘Unite’ from the Box Of Dub compilation LP. The same goes for other works of his like the EPs Streetlands (I can’t recommend this one enough!) and ANTIDAWN which, althouh more focused on the ambient side of Burial, still manage to retain the artist’s distinctively cold and ‘urban’ sound that’s become synonymous with his style. This can lead us to believe that the influence that Dubstep artists drew from Burial’s work isn’t necessarily related to the technical aspects of his work, such as the half-time drum beats or the intensive use of samples, but to his sound and the way he uses it to paint images of dark urban dreariness inside the mind of the listener, and that’s a kind of magic that still lasts to this day.

I want to end this article on a personal high note: the next handful of paragraphs were written by fellow Substack writer and personified underground music encyclopedia Stephan Kunze of the newsletter Zen Sounds. Unlike me, Stephan was lucky enough to be involved in the underground music scene in Germany when Dubstep first started to make waves outside of the UK, and that led him to write several pieces about this then-new and exciting style of electronic music during his time working as an editor for some of Germany’s most established music publications of the time. As far as he told me, this was an opportunity to dive back into the work of some of the artists that essentially made the genre’s golden era. For the rest of us, I think it might be the perfect chance to experience the same music from the perspective of someone who was around when their creators pioneered a genre whose legacy lasts to this day.

Classic Material: 10 Early Dubs

by Stephan Kunze (Zen Sounds)

It’s 2007, and Skream is playing a set of unreleased dubplates at Munich techno club Rote Sonne. No one in this small crowd of bass lovers has a clue how to dance to these weird halfstep beats, but the sheer physicality of the music, played on a huge system, makes the low frequencies vibrate in my belly, rattling my torso and my chest. I’ve been listening to dubstep for around two years, now I finally understand it. Back home, I start writing a glowing feature for German music magazine Spex on how dubstep became the most exciting sound of the hour.

Dubstep’s roots reach back to the turn of the millennium, when the genre slowly rose out of the ashes of UK garage. For many clubbers, its deep dub basslines and the dark atmosphere of the music felt like an antidote to UKG’s ‘grown & sexy’ vibes. But when some of South London’s bedroom producers – many of them former drum’n’bass heads – switched from swinging garage drums to 140 bpm halfstep beats, something magical happened. Like in many subgenres of electronic music, a brief experimental period of a few years followed the first underground explosion. Everything seemed possible.

After 2010, undoubtedly great tunes were still being released, but the genre became ever more formulaic. UK Funky took over London’s clubs, bringing back the Champagne-sipping UKG days. For the less dancefloor-oriented, but dubstep-influenced music of artists like Mount Kimbie, James Blake and Joy Orbison, the catch-all term ‘post-dubstep’ was coined. Many fans except for a few die-hards moved on. It was still three years until Skrillex and A$AP Rocky collaborated on “Wild For The Night”. Here are 10 dubplates from the golden era, way before dubstep went spring break.

01. Loefah - Root (DMZ, 2005)

DMZ was a formative label and club night in the 2000s dubstep movement, run by producers Digital Mystikz (Mala & Coki), Loefah and MC Sgt. Pokes. Loefah’s “Root” embodies that minimalist quality of early dubstep, with its sparse drums, hypnotic vocal sample and a wobbly bassline at the center of the mix. This is the sound of the legendary DMZ night in Brixton, South London, where people lined up around the block to get lost in hazy smoke and dark beats: “Not for publication. Dubplate, dubplate, dubplate…”

02. Digital Mystikz - Misty Winter (Soul Jazz, 2006)

In an early interview on Blackdown’s blog, the mighty Burial raved about Digital Mystikz:

“Their tunes go beyond other tunes straight into the heart of something else. You can’t fake that, it’s the real shit. (...) Some of those tunes are so good I can’t even listen to them, like ‘Misty Winter’.”

I don’t have much to add to that, but Mala and Loefah have remastered many of the early DMZ plates and released them on their Bandcamp pages in the last years.

03. Kode9 - 9 Samurai (Hyperdub, 2006)

One of the real pioneers and founder of the Hyperdub label that releases all of Burial’s music to this very day, Scottish producer and DJ Kode9 has an infinite catalog of influential tunes, from jungle to dubstep to funky to gqom- and footwork-inspired stuff. One of my favorites is this early ultra deep stepper that was first released as a B-side in 2006 and then included on his “Memories Of The Future” album with late vocalist The Spaceape.

04. Kromestar feat. Cessman - Kalawanji (Deep Medi, 2006)

Kromestar grew up just outside Croydon, dubstep’s birthplace in South London, regularly visiting the Big Apple record store. As Iron Soul, he produced instrumental grime; under his dubstep-oriented Kromestar alias, he first created this deep, dark and minimal anthem, co-produced with Cessman. It was the first release on Mala’s own label Deep Medi, which has an exciting catalog in itself.

05. Pinch - Qawwali (Planet Mu, 2006)

DJ Pinch was a fixture of the Bristol dubstep scene, and “Qawwali” the tune that put him on the map with its minimal, percussive drumwork and ritualistic undertone. Just a timeless classic, and also proof that Mike Paradinas’ experimental electronic label Planet Mu was involved with the dubstep scene quite early on.

06. The Bug feat. Killa P & Flow Dan - Skeng (Hyperdub, 2007)

Kevin Martin alias The Bug had been involved with all sorts of dub-adjacent music since the early 1990s. Bridging the post-garage gap by getting grime MCs Killa P and Flow Dan on his mighty “Skeng” riddim, this was one of the hardest tunes of that era (even harder than “Hard”). Played at every real dubstep night, even for many years after.

07. Mala - Alicia (Dubplate, 2007)

The most beautiful dubstep tune ever created. It’s a sped-up edit of Alicia Keys’ “Feeling U, Feeling Me (Interlude)” with some heavy drums put underneath the rhodes, guitar and vocals. Still way more downbeat than most of Mala’s output on DMZ and his own Deep Medi label, it almost sounds like a blueprint for The Weeknd’s early mixtape trilogy (the original versions, not the remasters).

08. TRG - Broken Heart (Martyn’s DCM Remix) (Hessle Audio, 2008)

Romanian producer Cosmin TRG’s original was great, but Martyn transformed it into a real steppers anthem. A Dutch drum’n’bass disciple that converted to dubstep in the mid-2000s, reportedly after hearing an early Kode9 tune, Martyn went on to produce an outstanding amount of great music, constantly crossing the bridges between dubstep, techno and jungle.

09. 2562 - Techno Dread (Tectonic, 2008)

2562 was the alias of Dave Huismans, another Dutch producer who also went under A Made Up Sound (a Source Direct track title, which again makes the jungle lineage visible). His underrated “Aerial” album combined dubstep beats with dub techno vibes, making visible the growing connections between the two scenes. (Just a few months before, minimal don Ricardo Villalobos had remixed Shackleton’s “Blood On My Hands”.)

10. Kryptic Minds - One Of Us (Swamp 81, 2009)

Originally a dark drum’n’bass outfit from Essex, producer duo Kryptic Minds made a hard cut in the mid 2000s and came back after a four-year break on Loefah’s Swamp 81 label with some of the heaviest, murkiest dubstep. The folks at Boomkat call their album “One Of Us”, which came out a few months later on their own Osiris imprint, “one of the last great dubstep releases”, and they usually get it quite right.

Thanks, Lorenzo! This was fun.